Five years after death, KC Royals’ Yordano Ventura is both revered and cautionary tale

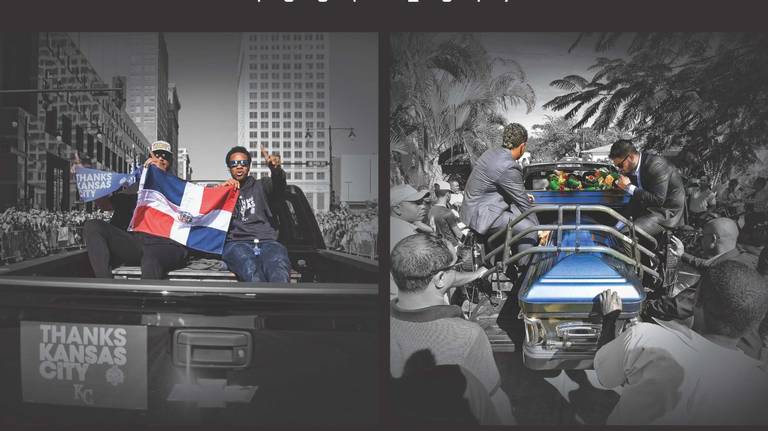

The photos together, at once contrasting and parallel, are so compelling that Moore turned the depiction toward a visitor in his Kauffman Stadium office earlier this week and swiveled his desk chair to gaze at it for minutes as he spoke.

Two eternal images of Yordano Ventura are enshrined side by side in a frame on Dayton Moore’s desk. And, indeed, they do frame the trajectory of the shooting star gone too soon, after too much too soon, and the cautionary tale left in his vapor trail. The photos together, at once contrasting and parallel, are so compelling that Moore turned the depiction toward a visitor in his Kauffman Stadium office earlier this week and swiveled his desk chair to gaze at it for minutes as he spoke. On the left in the frame is a photo of Ventura on Nov. 3, 2015, holding up a flag of the Dominican Republic with his right hand and signaling No. 1 with his left on the back of a truck in a motorcade in downtown Kansas City after the Royals won their first World Series in 30 years. On the right is a photo of Ventura on Jan. 24, 2017, out of view in a casket at the feet of teammates Salvador Perez and Eric Hosmer on the back of a truck bearing flowers and escorted by mourners to his burial in Las Terrenas. “You have a parade of 800,000 people, celebrating a world championship with Yordano Ventura; his competitive spirit is one of the reasons we were able to win a world championship — that fearless competitive spirit that he had,” said Moore, the longtime Royals general manager who was named club president in September. “And then a little over two years later, he’s in another parade going to his resting site in Las Terrenas.

“It just speaks to the brevity of life, and how fragile life is. The brevity of life and the importance of good choices. And that choices have consequences.” Still looking at the photos, Moore called Ventura one of the most beautiful people he’d ever known, and added, “That moment when he died has had an everlasting impact on many of us. And I’m not sure we really understood the psychological damage that our organization experienced, and I still think we’re trying to recover from that, in some ways.” Five years ago Saturday — January 22, 2017 — the audacity that underscored Ventura’s career and mirrored his life, and the heedlessness that marked his final months, led to Ventura’s death. That sense of abandon helped convince Ventura to otherwise inexplicably leave a festival in Ocoa in the middle of the night and embark on a three-hour drive through a treacherous mountain road he’d never driven to see his estranged wife, María del Pilar Sangiovanni. In that act, Moore lamented, his fearlessness “took his life.” But that didn’t happen entirely in a vacuum, either.

To a certain degree, Moore and the Royals understood Ventura had been veering since they signed him to a five-year, $23 million contract extension in April 2015. Certainly, he was partying more and more, splurging and in the thrall of the clearly manipulative and arguably toxic Sangiovanni, whom Ventura’s family blames for his estrangement from them. (Their marriage was annulled in 2018.) That’s why when Moore met with Ventura at the end of the 2016 season, he told him he loved him, that “we needed to help him” and encouraged him to stay in Kansas City that offseason. He even told Ventura he could live in his home. Or with Rene Francisco, now the Royals’ vice president of international operations who had signed the 17-year-old Ventura for $28,000 in 2008. Ventura didn’t want to do either, though. And Moore now says with sadness that if he had it to do over again he would have demanded Ventura stay instead of offering it. “He wasn’t ready to make good decisions for his personal life on a consistent basis,” he said. That was exacerbated by a contract, Moore believes, that led him toward in some ways loving “the lifestyle of a major-league player more than being a major-league player … (and) pursuing all different types of luxuries and lifestyles.” “That money gave him a security,” he said, “to where he never really understood consequences.” On the night of his death, in fact, Ventura wore no seat belt in the tricked-out Jeep that was detailed in Royal blue and adorned with “YVentura” in its front grille and headrests — an extravagance that epitomized that contractual dividing line in the course of Ventura’s life. “Everybody knew whose Jeep it was when he drove it,” MC Customs of Miami wrote in publicity material after delivering the vehicle to Ventura between his signing of the extension and the Royals winning the 2015 World Series. And everybody, alas, knew whose Jeep it was after it smashed through a guardrail and he died in Juan Adrian. The abrupt, tragic ending sent shock waves through the Dominican and shattered many in Kansas City, which was a crucial part of why Moore allowed The Star to embed with the Royals’ traveling party to the Dominican for the funeral, and speaks to why he is so candid now. It was a decision then that few, if any, other pro sports organizations would likely even entertain. And that’s an important and revealing part of this story, too, about how an organization that feels like such a part or our lives includes or doesn’t include us all in times of joy or crisis in particular. You saw it that night in the overwhelming images of Danny Duffy, Christian Colon and Ian Kennedy going to Kauffman Stadium to console fans. Or was it the other way around? Either way, the scene still could make you weep, both for its sheer agony and the beauty of the broader message. Kansas City “is our family, too: The good, bad and the ugly should all be written about so we can celebrate it and learn from it and be inspired by it,” Moore said, turning back to the photo and adding, “I want people to be inspired by Yordano Ventura: his fearlessness, and his toughness and his aggressiveness. “But then you’ve got to throttle it down off the field. And (consider) the importance of having good people around you that can speak truth into your life and help manage you and mold you and shape you.” That cautionary tone has a particular application in the Dominican, where the Royals Academy through which Ventura and many others (including Perez) acclimated to the organization added driver’s education to its programs in the wake of Ventura’s death. The scene of his crash also was piercingly familiar in the Dominican, which was classified in a 2015 World Health Organization study as the most dangerous place to drive in the Americas. In spellbinding fashion in Game 6 of the 2014 World Series, Ventura paid homage to his friend Oscar Tavares of the St. Louis Cardinals and the Dominican, where Taveras died along with his girlfriend in a crash two days before. Before Moore got the miserable news about Ventura that morning five years ago, in fact, he received a call about the death of Andy Marte in an unrelated car crash in the Dominican. Marte was the first player Moore signed after becoming the director of international scouting for the Atlanta Braves in 2000. As he still was reeling from that call, he heard from MLB Network’s Jon Heyman as Moore was getting ready to board a flight to Atlanta from Kansas City International Airport. When Heyman asked Moore if it was true about Ventura, Moore was sure he must have meant Marte. But it was true about Ventura, the circumstances of whose death remain shrouded in several ways. The toxicology report never was made public and provided only to his family and attorneys, authorities in the Dominican Republic told The Star three years ago, and still has never been released. Moreover, the remaining part of Ventura’s contract, $20.25 million, had not been paid three years ago and is understood to remain unsettled among what may be other lingering legal matters. Ventura’s 8-year-old daughter is believed to still be listed as the sole heir of his estate, according to court documents obtained three years ago that said she had received a life insurance payout held in a protected trust. The Royals declined comment on those matters. But they continue to offer unspecified support to Yordano’s mother, Marisol, among other family members in Las Terrenas. Through Royals Charities, they also have upgraded the field on which Ventura grew up playing. They hold offseason clinics (but for interruptions of the pandemic) there, said Jeff Diskin, the Royals’ director of professional and community development who previously served as their coordinator of cultural development, with an emphasis on supporting Latin American players.

Whenever a Royals delegation visits, they nearly always pay respects at Ventura’s grave site. That’s not far from where Moore and the Royals lent comfort to the family, and the people of Las Terrenas and perhaps even the nation itself, when they arrived for the funeral and then walked miles to the burial in the harsh heat of the day among the Dominican people. I’ll never forget Moore taking the hands of Ventura’s family near his casket in the home and telling them how much the Royals loved him and that they were “proud and honored to share in this sorrow and pain with you.” The grave site also isn’t far from where Ventura grew up in poverty and uncertainty that forged an indomitable strength that helped him will his way to the major leagues. That came with a certain swagger that struck about anyone who ever met or saw him. Moore remembers his first real interaction with him was in 2011, when Ventura was playing for Class A Kane County and throwing a bullpen session the day Moore came by.

“And he came up to me afterwards like, ‘Yeah, you liked what you saw,’” Moore said, smiling. “‘You know I’m the man.’” That temperament came to enchant teammates and captivate the city, particularly during back-to-back World Series runs in 2014 and 2015. That included at times seeming out of control on the field, particularly amid a series of altercations in 2015. After an episode with Angels superstar Mike Trout, Moore recalled getting a call from the commissioner’s office to tell him Ventura was being fined and essentially asking “does he not know that’s Mike Trout?” Outraged, Moore said, “‘You don’t know who Yordano Ventura is. Yordano Ventura is fighting for his life every single day as it pertains to staying in this game and from where he came.’” Overcoming what he did also was part of what Moore considers a false invincibility Ventura came to feel, on and off the field.

Still hoping to find a way to help him, Moore rejected several potentially otherwise appealing trade offers for Ventura in the offseason between 2016 and 2017. “He was just too complex …” said Moore, who believed it would have been hard for him to fit in elsewhere. “He needed to stay here. We needed to get him right.” Even if he sometimes wonders what might have been done differently to get Ventura right, Moore is certain the Royals could not have cared more than they did. And that’s one of the reasons he has these pictures framed now and refers to them often when he speaks with young players or other groups. Both because of how Ventura lived and how he died.

It’s all something to honor and mourn and maybe most of all try to learn from, as Moore put it, whether in surrounding yourself with the right people or not being afraid to seek counsel. Five years later, this is another way Ventura lives on. “I think about this situation more than I ever think about our World Series championship,” said Moore, who, in fact, said he thinks of Ventura daily. “Because I learned more from this situation than I ever learned from that.”